Exhibition Opening: June 2nd 2023, 7 pm

Opening Hours: June 5th – 16th, 3 – 6pm; Saturday & Sunday closed

On February 15th, 1894, a bomb exploded at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England. The device detonated prematurely, killing the perpetrator carrying it and leaving behind a mystery surrounding his motivations. Today it is believed that the observatory’s Master Clock, by then the world’s clock, symbol of the British Empire’s status as a global superpower and its technological and scientific advancement, was the likely target of the attack.

Tensions between objective, universal time and its individual perception are at the center of the exhibition. Shown are several objects and spatial interventions dealing with keeping, spending, stretching and killing time. Ancient organisms live in symbiosis with modern satellite technology, split-second decisions leave permanent imprints and sculptural artefacts get frozen before melting away.

Daniel Stempfer was born in Austria and lives and works in Hong Kong. His sculptures and installations often deal with temporary phenomena, the traces they leave behind and the re-creation of past events from fragmentary evidence.

His works were shown at Traklhaus Salzburg, Salzamt Linz, Callirrhoë Athens, MMCA Seoul, MMK Frankfurt, Kunstverein Wiesbaden, Mediterranea Biennale Tirana, Feyerabend Hong Kong, W139 Amsterdam, Art Center Ongoing Tokyo, Swimming Pool Projects Sofia, Gallery Soy Capitán Berlin, basis Frankfurt, among other places. He studied at the Glasgow School of Art and at Städelschule Frankfurt am Main with Prof. Willem de Rooij, where he graduated Meisterschüler in 2013.

On Exploding Time

Daniel Stempfer has been making clocks, but one cannot help but wonder whether he is more interested in keeping time, or exploding it.

The artist brings our attention to an odd historical event, his recent obsession, the enigmatic bombing attempt of the Shepherd Gate Clock at the Greenwich Royal Observatory in 1894, resulting in a premature detonation and untimely death of the short-lived terrorist Martial Bourdin. For Bourdin, his time was up. But for the British Royal Observatory and its symbolic clock, “universal time” moved on universally—unscathed and indeed ever more internationally entrenched, to be exploded, perhaps, another time. We are left with an event that, at once, marks one’s finitude and everyone else’s continuity. That is to say, in effect, we are led to consider, what happens when the singular challenges the universal? How might we reconcile the immemorial continuum of Time against the significance of that one time resurrected, stretched, frozen, and displaced beyond temporaneity? And how do we conspire to kill the other, and pick up its pieces; to reassemble it, to slow it down with the heat of our own contemporaneous presence? At the exhibition space, we bear coeval witness as if at the scene of a crime for which we are complicit.

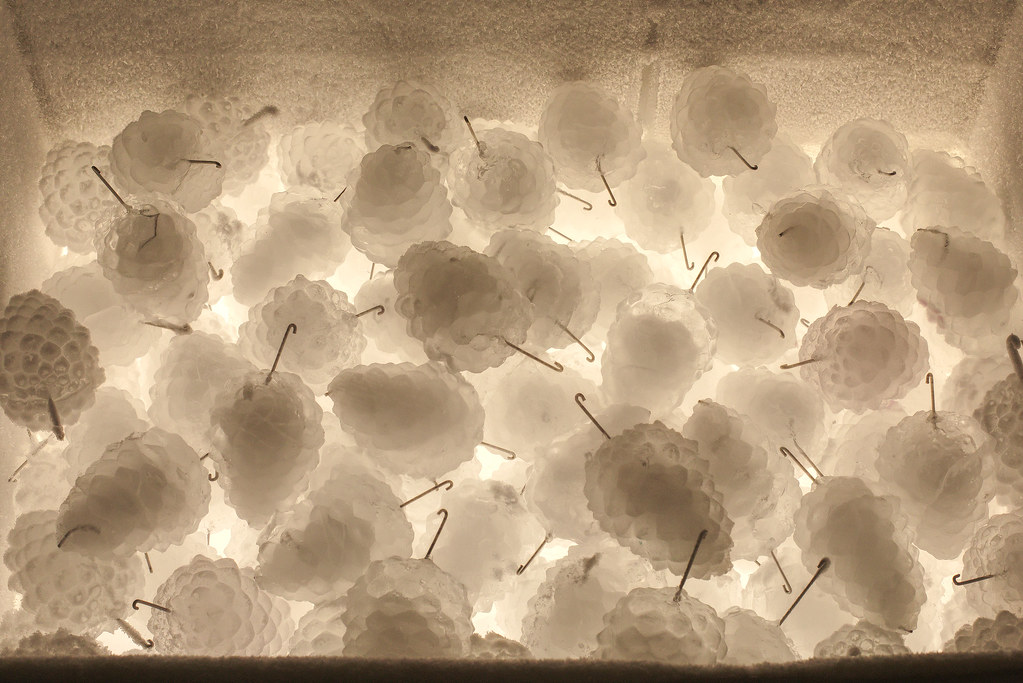

“The whole world is just one big clock,” wrote Alfred Gell, the British anthropologist of time, “but it is one which different people can read very differently – because what we can see, out there in the objective world, is only, so to speak, the hands of the clock, but not the clock-face in relation to which, and to which alone, the configuration of the hands assumes its particular temporal meaning.” In About Time, what we can see are two clocks, or rather, two clock hands. On the one hand, dissolving seconds tick ever slower across a spectral clockface. Its design is reminiscent of the Shepherd’s clock of a past imperial age and its mechanics is driven by an array of pinecone weights of concrete and ice—the latter melting before our eyes—the weight of time slipping away. On the other hand, the rigid carapace of a horseshoe crab—the exoskeleton of a prehistoric fossil in its unhurried rotation through four hundred million years of evolutionary history—is synchronized to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) by means of a satellite calibrated to the resonance of a Cesium-133 atom accurate to three billionths of a second. Put together, the time piece becomes the convergence of opposite ends of time scales from billions of seconds to billionths of a second within a singularity.

Between the two clocks, Stempfer’s other works present us with a landscape concerned less on time lost or regained, and more about how to put back together its timeless remnants. Three deployed airbags, two driver-side and another passenger-side, spectral relics of three separate collisions point to accidental, singular time—preserving, for each, that one time. In another piece, the patinaed remains of an opened pod of the flame of the forest (Delonix regia), a cosmopolitan arboreal species native to Madagascar, speaks to the artist’s own immediacies. Electroplated with copper harvested from local construction scrap metal outside his Hong Kong studio, the metallic pod asks us what we make of a fallen organic body materially remediated—and thereby preserved—through the inorganic growth of second-life copper crystals. To put Stempfer’s various time pieces together is to oscillate between a conceptual explosion of universal time and the quiet suspension of its more intimate instances. In each case, the ends and beginnings are twisted together in a play between immortalized death and vicarious life. And for a moment, the brokenness of time passes us by.

It is said that the universe of all things, including time itself, began with an originary explosion—one that has led up to now. Everything since, in its unidirectional diffusion, we might say, is history. Yet, Stempfer’s various time capsules seem to take us from history back to the singularity. What gives a single moment its meaning? And what memories can materials make? How might we rewrought the clockface of the world, or should we simply stop counting and, freely, kill time? About Time leaves us no answers, but continues to ask of us to capture that Kantian category, to delve within history, to freeze it in its tracks, to find a face in its clocks so as to grapple for its meanings, as a question for the now. In that sense, it’s about time.

Chris Cristóbal Chan

2 June 2023